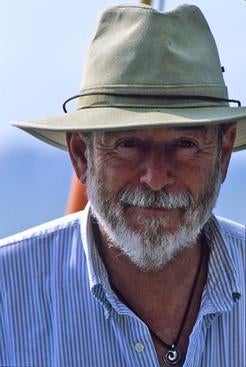

Exequiel Ezcurra will receive the 2020 Award for Science Diplomacy by the American Association for the Advancement of Science for his leadership in bringing together research, education, outreach, and policy in service of environmental protection, particularly at the United States-Mexico border.

Ezcurra, a professor of ecology in the Department of Botany and Plant Sciences at UC Riverside, studies the ecology and conservation of coastal deserts and drylands with particular emphasis on the Sonoran Desert, Baja California, and the Gulf of California. Throughout his 30-year career, Ezcurra has gone out of his way to ensure that his research informs scientifically sound policy.

“Exequiel’s activities as a science diplomat have been nearly career-long,” said Norman Ellstrand, a UC Riverside distinguished professor of genetics and Jane S. Johnson Endowed Chair in Food and Agriculture, who nominated Ezcurra for the award. “Most notably, he has worked hard to promote governmental action to protect the environment, most often at the U.S.-Mexico border, but often far beyond.”

One of his most prominent achievements is the establishment of the first environmentally protected area along the U.S.-Mexico border, the El Pinacate and Gran Desierto de Altar Biosphere Reserve. The area is now also a United Nations World Heritage Site and a UNESCO Biosphere Preserve.

Ezcurra, originally from Argentina, was performing research in the rainforests of southern Mexico when the opportunity arose to study the Gran Desierto in the northern state of Sonora for the Mexican government.

“The day I arrived in Sonora it was raining and the smell of the creosote brought back the sounds and smells of my childhood in Argentina,” he said. “I loved the place!”

As he did research that would become his doctoral dissertation, Ezcurra got to know people on both sides of the border, along with the border’s unique environmental, social, and economic issues.

“Without realizing it, I started working for the protection of the borderlands,” he said. “That’s how I started working with conservationists, politicians, and the Papago Nation.”

In 1992, Mexican president Carlos Salinas de Gortari signed a decree protecting Gran Desierto. U.S. Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt attended the ceremony to acknowledge the bi-national effort required to preserve the area.

Through this work, Ezcurra developed strong relationships with the United States National Parks Service and Fish and Wildlife Service, as well as with the head of the Canadian Wildlife Service. As Mexico’s director general of natural resource protection in the early 1990s, he leveraged those relationships to help create the Trilateral Committee for Wildlife and Ecosystem Conservation and Management to protect wildlife along the borders of all three countries. The Trilateral Committee, founded in 1995, still thrives today.

Ezcurra is also proud of his efforts to reintroduce the California condor to Baja California. He said there are now more than 60 condors in the region.

Ezcurra came to UC Riverside in 2008 as the director of the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States, or UC Mexus, a bilateral research initiative to build cross-border academic collaboration between the U.S. and Mexico. He served in that role for 10 years and tripled the number of graduate students from Mexico in the UC system.

Ezcurra is also a fellow of the Ecological Society of America and corresponding fellow of the Mexican Academy of Sciences. He has developed two museum exhibits and an award-winning film on the Sea of Cortés. He also served as Scientific Chair of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, and as president of Mexico’s National Institute of Ecology.

His current research projects tackle the past, present, and future of climate change. Ezcurra is working with researchers from several other universities to understand a mangrove forest recently discovered 200 miles from the ocean in southern Mexico. Mangroves are a coastal species, so their discovery that far inland and so many feet above sea level means the ocean must have once reached that far.

Ezcurra’s group is investigating how rapid sea-level rise during a warm period, known as an interglacial, around 125,000 years ago brought mangroves that stayed when the ocean retreated with the next glacial period. Sea rise was much higher and quicker in past interglacials, but with less human toll because no coastal cities or ports existed.

“The difference is 125,000 years ago we were not responsible for sea level rise,” he said. “Now we are.”

Another project with colleagues at the University of Guadalajara will examine digitized ancient and early colonial writings from Mexico called codices to explore the history of cactus and agave domestication in Mesoamerica.

“None but Mexican societies have domesticated them as fundamental cornerstones of agriculture,” he said, noting prickly pear cactus and agave were domesticated before corn, and have always remained a staple crop when it is too dry to grow corn, beans, or amaranth.

“These stalwart crops were and are the equivalent in Mesoamerica of olives in the Mediterranean,” he said.

Ezcurra hopes to encourage their use as crops able to flourish in the hotter, drier climate of our warming world.

The award will be presented February 16 at the American Association for the Advancement of Science's annual meeting.