Everything you have been told about home composting is wrong. At least, oversimplified.

That’s what you’ll conclude after you spend some time with UCR postdoctoral researcher and Master Gardener Clifford Morrison. He’s already got a Ph.D., in chemical and biological engineering, but if they’re ever handing out doctoral degrees for composting, Morrison will be among the first to collect his scroll.

For Morrison, breaking down food scraps and other organic matter into a rich soil is not only the climate-friendly thing to do; it’s chock full of tantalizing science. And it’s a perfect outside-the-lab, practical application of his academic research, in which he seeks to use microorganisms in environmental and agricultural solutions.

“Both my research and my involvement in composting are united by this core principle: utilizing environmental microbiology as a tool to solve real-world problems and promote sustainability,” Morrison said.

Repurposing food waste — banana peels, coffee grinds, that browned head of lettuce in the way-down refrigerator drawer — has increasingly become a cause célèbre. A state law aims to reduce organic waste in landfills by 75%, and food waste — environmentally friendly when properly composted — produces methane gas when compressed without oxygen in a landfill. Methane is 84 times more harmful to the environment than carbon dioxide.

“Put simply, composting is like cooking a special recipe for the soil,” said Morrison, who works in the Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering in the Marlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering. “What intrigues me the most is how this process, which occurs naturally, can be optimized through human ingenuity. By engineering it to be faster, more efficient, and more productive in our own hands, we can significantly enhance its benefits.”

Morrison, 32, who was a first-generation college student, recalls a childhood in rural, wooded northeast Texas, near Shreveport, Louisiana, that spurred an interest in natural processes, then gardening and composting, “witnessing firsthand the breakdown of organic matter and its revitalization into nutrient-rich soil.”

During his four years in Riverside, he graduated from the University of California Cooperative Extension Master Gardener program , then founded its composting effort at the Master Gardener’s Grow Lab, a Riverside plot used for horticultural experimentation. He volunteers there every Saturday for several hours.

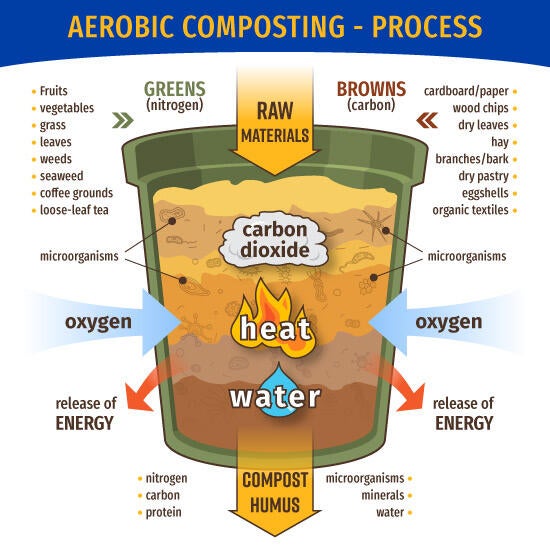

Describing the science of composting to Master Gardener trainees, Morrison defies conventional composting wisdom. Common practice holds that three parts brown should be combined with one part green. Carbon-rich “brown” includes leaves, old newspapers, and cardboard; nitrogen-rich “green” includes kitchen scraps, coffee grounds, and grass trimmings.

Morrison says “hot composting” — the fast-acting dynamic that yields rich compost — means not only the correct green-to-brown ratios, but it also involves the right amount of moisture and aeration. This provides an environment in which microorganisms thrive, breaking down organic matter. That breakdown, in turn, creates heat, which further speeds the process.

“Composting, to me, is a fascinating intersection of microbiology and biological engineering. Just as the brewing of beer or the making of yogurt harnesses microbiological processes for human benefit, composting represents a deliberate intervention in the natural decomposition cycle,” he said.

If there are any doubts who’s right — the three-browns-to-one-green YouTube gardening pundits or the scientist Morrison — consider Morrison’s results. Within about three days, his 3-foot-by-3-foot pile of leaves and grass billows steam when prodded with a pitchfork. Within two to three weeks, the mixture has been converted into what gardeners call “black gold” — dark, crumbly, nutrient-rich, earthy-scented compost.

“His approach is much more scientific than I had been used to, and he gets great results,” said Lucy Heyming, a Master Gardener and owner of the five-acre Riverside property that includes the Growlab. “He increased and expanded my knowledge of the science behind the composting process, the various microbes, and steps involved in order to obtain a product that is healthy for our soils because of the addition of the nutrients found in compost.”

Morrison has turned his corner of the Growlab into a veritable compost factory, generating more than 2,000 pounds of finished compost in the past two years. A portion of the compost is sold at Master Gardener events.

“Volunteering at the Grow Lab brings me a unique sense of satisfaction that complements what I experience in my regular job,” he said. “My involvement at the Grow Lab allows me to connect directly with the local community. This direct engagement is incredibly fulfilling. I'm not just sharing knowledge; I'm actively participating in creating a more sustainable environment.”

Morrison plans to expand his “compost activism” by advocating for local composting policies, securing subsidies for composting bins, starting community gardens and composting sites, and teaching the science of composting at school and community events.

Editor’s note: The UCCE Master Gardener Plant Sale and Compost Workshop will be April 13 from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Morrison will be there leading composting workshops — try and stump him with your most complex compost questions. For more information, visit this Facebook posting by the UCCE Master Gardeners of Riverside County.

Extracurricular is a new ongoing series spotlighting hobbies, interests, and passion projects by UCR students, faculty, and staff members. If you have suggestions for future profiles please contact news@ucr.edu