Scientists often spend their spare time engaging in a mix of intellectually stimulating and relaxing activities. Many enjoy reading fiction, popular science, or philosophy, while others pursue hobbies that align with their skills, such as puzzles, coding, or writing.

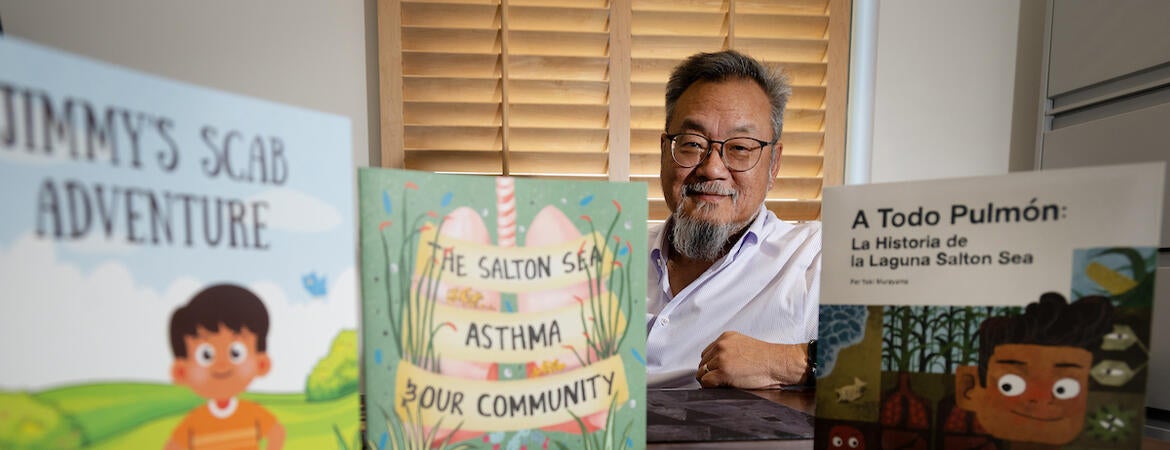

Dr. David Lo, a distinguished professor of biomedical sciences in the UC Riverside School of Medicine, uses his leisure time to explore a powerful medium to bridge science and community — comics. With a passion for using art to communicate complex health issues, particularly those affecting communities in Southern California, Lo has spearheaded a series of graphic narratives that make public health information more engaging, accessible, and memorable. In this Q&A, he shares how the project began, the creative process behind the health-focused comics, and why visual storytelling is a critical tool for community empowerment.

Q: What inspired your interest in graphic narratives?

I’ve always been drawn to graphic storytelling. I teach a course on graphic narratives in medical humanities and go to Comic-Con every year. Comics are a unique way to tell stories — especially stories about health and science — that engage people differently than traditional formats.

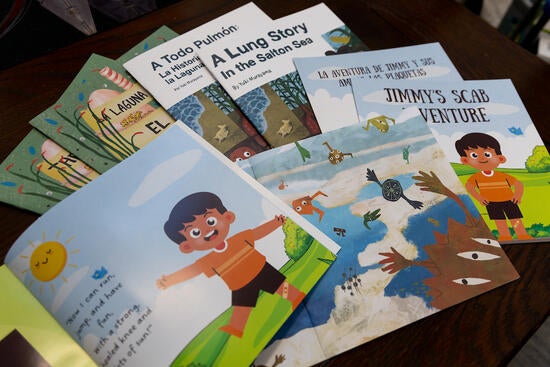

I’ve worked with medical students who are both scientifically grounded and artistically creative. For example, one student, Zayan Musa, created a children’s comic on how the body heals wounds. She wrote it in rhyme and even translated it into Spanish — also in rhyme. It was clever and educational, and my Mexican American students told me they learned scientific vocabulary in Spanish from it.

Now I work with both undergraduates and medical students on similar projects. One group is tackling air quality and health in the Inland Empire, particularly the impact of diesel pollution from warehouses and distribution centers. Another group is developing a comic on mental health for children. The format allows us to reach people in ways dry pamphlets or dense text simply can’t.

Q: Are you an artist yourself?

I’d like to be! I practice drawing, but I’m nowhere near as skilled as the artists I work with. Still, I have a deep appreciation for visual storytelling. Comic books and graphic novels are powerful. You don’t need a superhero to explain something like kidney stones. Graphic novels often tell deeply personal stories — about living with schizophrenia, coping with cancer, and so on. These are compelling and relatable narratives.

Using images lowers the barrier to entry. You don’t need to be fluent in a particular language to understand the message. The visual format can transcend language and literacy levels, making it especially valuable for community health outreach.

Q: How did the current project get started?

It began with the idea of using comics to communicate research about the Salton Sea — particularly the health effects on nearby communities. We wanted to find a way to share environmental and medical information in an engaging, accessible format.

Some years ago, I helped teach an illustration course at CalArts. As part of that course, students created proposals around the health effects of the Salton Sea. Two of those proposals stood out — they had real potential to become full short comics that told compelling stories while conveying scientific and medical information. So, we paid those artists to turn their ideas into fully developed comic books.

We made sure the comics were available in both English and Spanish by working with local translators. The two artists had distinct styles and perspectives, which made the stories even more engaging. Despite their differences, both versions communicated core messages about environmental issues, public health, and the importance of things like seeing your doctor and taking prescribed medicine.

Q: What kinds of topics do you want to explore going forward?

Health is still our starting point. Right now, we’re working on a project about high arsenic levels in groundwater in the Coachella Valley. We’re also exploring air quality issues and how wildfire smoke and diesel exhaust impacts health. From there, we want to address broader issues, like community health disparities, without using jargon. Instead, we tell real stories about people’s experiences and challenges.

We hope to cover many topics: medicine, biology, public health, ecology, even aspects of policy and social organization. We haven’t delved into deep philosophical issues yet, but everyday problems that matter to communities are at the heart of this project.

Q: How much does it cost to make one of these comic books?

They’re printed on high-quality paper, so each copy costs just under $10. We’re currently looking to attract more donations to help cover printing costs. We now have a donation button on our website.

Q: Who is your intended audience?

Ultimately, it’s everyone — but our primary focus is the Inland Southern California community. Many of our medical student authors come from this area and are passionate about serving their communities. So, while the topics can be broadly relevant, we aim to respond to local needs.

If someone in the community says, “We need a comic on this topic,” we can be nimble and create it. We’re not trying to be a big publishing house. Instead, we’re responsive and grounded in real community concerns.

Q: Can you walk us through the process of making a comic?

It starts with an idea and a script — not just good drawing. Like a movie, you need a storyboard, but before that, you need a strong script. The script lays out who’s talking, what the setting is, and how the narrative flows — indoors or outdoors, day or night, who’s speaking to whom.

Then comes layout: Are there small panels or full-page scenes? How do you guide the reader’s eye? If the artist and writer are the same person, that’s simpler. But if they’re separate, they have to collaborate closely. I often provide reference images and give feedback on page layouts.

The visual storytelling must keep readers engaged, show motion, perspective, and emotion. Are we seeing things through the main character’s eyes or from above? All these choices matter. The whole process can take a few months, depending on the complexity, revisions, and ensuring medical accuracy.

Q: Once printed, how are the comics distributed?

Right now, our goal is to make them free for clinics. We deliver boxes to clinics, who can hand them out to kids and families. We also distribute them at community events and seminars. We haven’t set up a formal mailing system yet, but the comics are always free.

So far, we’ve completed three comic books, each in English and Spanish, making six total versions. Several more are in development.

Q: What are your hopes for the future of the project?

I hope we can continue using comics as an effective communication tool — mainly for medical and scientific information, but also to empower communities. These comics can help people engage with their legislators, understand public health issues, and make informed decisions.

It’s also about giving the university a tangible presence in the community. Too often, people feel that the university is isolated. This project allows us to show that we’re here for a reason — and that we’re listening.

In the future, we’d love to get more input from the community about what topics are important to them. We’d also like to raise funding to commission new comics on valuable topics. Right now, we’re focused on inland Southern California, simply because it’s manageable for production and distribution. But we’re open to growing the project.

We’re developing an editorial board to help manage the increasing workload, especially ensuring medical accuracy with support from our clinical faculty. Originally, the project was supported by a Center for Health Disparities grant, but now it operates under the broader umbrella of BREATHE. Even though BREATHE started as an air quality initiative, the name lends itself to a wide range of interpretations, and that’s exactly what we’re doing with it.

Header image credit: Stan Lim, UC Riverside.