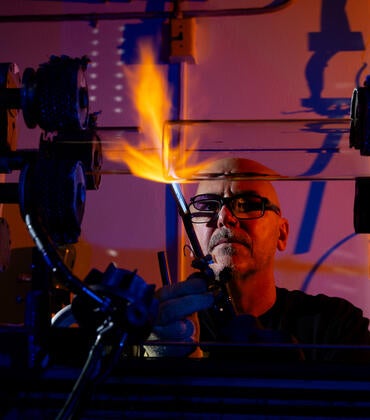

At UC Riverside’s CNAS machine and glass shop, ingenuity meets precision. Open to the campus, the shop supports projects across physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering, producing everything from quick lab fixes to complex experimental systems.

That hands-on support recently took visible form in a custom-built cloud chamber now used in physics courses and outreach. Boerge Hemmerling, an associate professor of physics and astronomy, uses the device to bridge the gap between abstract theory and physical reality.

“Students hear about radioactive decay, but it can feel distant and theoretical,” Hemmerling said. “When they see the particle tracks forming in front of them in the cloud chamber, the concept clicks. It turns an equation into an experience.”

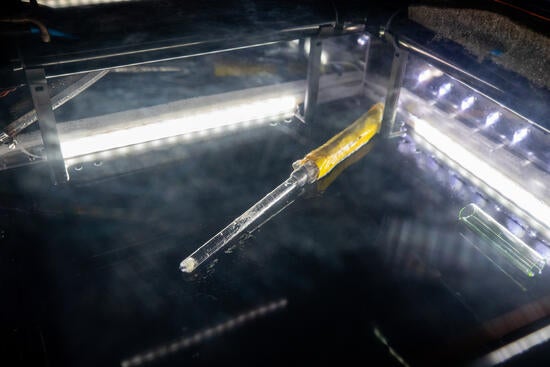

The cloud chamber reveals the normally invisible world of radioactivity by transforming particle motion into delicate, fleeting trails. Heated ethanol evaporates from a top-mounted trough, filling the chamber with vapor. When radioactive particles pass through the chamber, they act as nucleation sites, causing the ethanol vapor to cluster into wispy tracks that briefly hang in the air.

For Hemmerling, the value of the chamber extends beyond novelty.

“It changes the energy in the room,” he said. “Instead of just describing an invisible process, you’re letting students watch nature do something extraordinary in real time. That kind of moment sticks with them.”

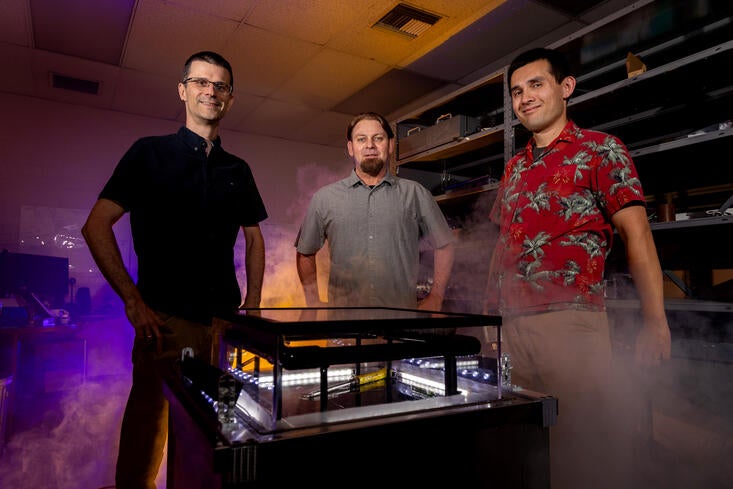

The chamber was fabricated largely in-house by research engineer Eric Gazelle, who estimates the project took about 70 hours spread over the course of a year.

“It was a side project we worked on between other jobs,” Gazelle said. “But it ended up pulling together almost everything we do here — machining, welding, 3D printing, electronics, and assembly.”

Gazelle and fellow research engineer Jay Lefler manage a steady stream of custom work, typically handling 10 to 20 orders a month. Some requests involve minor adjustments, such as resizing a single part. Others require rebuilding entire systems. In one recent case, Gazelle reverse engineered the top of a damaged scale; he redesigned it in CAD, 3D-printing replacement components, soldering new connections, and fully restoring the unit to working condition.

That versatility defines the shop’s role on campus. Faculty submit requests, consult with Gazelle and Lefler on design and cost, and receive custom-built solutions, often at a fraction of commercial prices.

“Often we can do it for half the cost, and we can modify it as the research evolves,” Gazelle said.

Lefler believes the shop’s CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machines are a major asset. Unlike conventional tools, CNC machines can precisely reproduce complex parts, improving consistency and saving time.

“You can tackle pretty much any machine shop job on these machines,” Lefler said.

In one recent project, the team designed a custom vacuum chuck to hold fragile plastic components during cutting. Standard clamps would have cracked the material, so Gazelle and Lefler created a solution that secured the pieces without damage.

The shop supports research needs across campus, with graduate students frequently requesting specialized equipment ranging from bee observation tanks to renewable energy components. All work is funded through departmental research grants using a recharge system.

“We make it, the researchers pay with their grant money, and it’s seamless,” Lefler said. “If our researchers need it, we will make it.”

The workshop, which opened on campus in the late 1960s, blends old and new. Lathes from the 1960s sit alongside CNC machines, welding stations, sandblasters, and an electronics bench. Vacuum pumps line one wall, many awaiting routine rebuilding after heavy lab use.

“We’ve made centrifuges for experiments with fruit flies, clamps for delicate equipment — almost anything,” Gazelle said. “The only hard no I remember was a 100-foot telescoping pole someone wanted to drive down the road.”

While UCR operates another machine shop in the engineering complex on campus, the CNAS machine and glass shop fills a different niche.

“The shop in engineering focuses on teaching,” Gazelle said. “Here, we focus on getting experiments working.”

Making the invisible visible

When the cloud chamber is rolled into a room, it appears unassuming — a compact metal-and-acrylic box on wheels. But once powered on, faint white streaks begin to flicker inside, tracing the paths of radioactive particles in real time.

Robert Sanderson, an instructional laboratory manager in UCR’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, helped conceive the chamber as a portable teaching and outreach tool. His goal was simple: a device instructors could roll into a classroom, plug in, and use immediately.

“Inside the chamber, a supersaturated alcohol vapor hovers above a cold plate,” Sanderson explained. “When radioactive particles pass through, they trigger condensation, creating visible trails. Alpha particles act as nucleation sites; as they move through the vapor, they leave behind tiny tracks of condensed alcohol — the clouds you see.”

The radiation source is a small sample of thorium, a naturally occurring metal with very low activity. With a half-life of about 75,000 years, thorium emits radiation slowly enough to be safe for demonstrations. Occasionally, cosmic rays from outer space streak through the chamber, producing long, straight tracks.

Hemmerling explained that cloud chambers played a central role in early 20th-century physics, helping scientists identify particles and understand radioactive decay. Today, the chamber serves a primarily educational mission.

The chamber built at UCR recently debuted in Physics 10: How Things Work and is already in demand for open houses and outreach events. Hemmerling plans to incorporate it into additional courses and hopes to expand its role in public engagement.

While demonstrations for younger students require additional approval due to the radioactive source, Hemmerling sees strong potential for outreach in middle schools.

The cloud chamber project relied on collaboration and practical problem-solving. Rather than starting entirely from scratch, Sanderson proposed adapting an ice cream maker as the base, simplifying construction while preserving functionality. Working closely with the machine shop staff, the design evolved through testing and iteration.

Gazelle and Lefler fabricated most of the system’s components, including the ethanol tank and trough, aluminum support plates, LED lighting, internal shelving, pumps, heaters, and power supplies. Several parts were 3D printed, reducing machining time and allowing rapid customization.

“There’s always a balance,” Gazelle said. “You want flexibility, but you also have to work within the limits of the machines, the budget, and what’s practical to build.”

The result is a versatile teaching tool that brings fundamental physics to life.

“Radioactivity is everywhere,” Hemmerling said. “Thanks to a handful of very skilled engineers and a simple box on wheels, students at UCR can finally see radioactivity happening one particle at a time.”

Header image shows Eric Gazelle (left) and Jay Lefler in the CNAS machine and glass shop at UC Riverside. (UCR/Stan Lim)