UC Riverside’s herbarium is helping create an unprecedented resource for scientists studying how climate change is affecting California’s plants.

The herbarium has joined a consortium of 28 other herbaria, universities, research stations, natural history collections and botanical gardens digitizing their plant collections. By 2022, they will have built a free public database featuring images and detailed data about more than 1 million specimens.

This $1.8 million project was funded by the National Science Foundation to answer questions about whether a warming climate is altering plant flowering and fruiting patterns.

“Some studies suggest flowering time is getting earlier as the climate is getting warmer,” said herbarium director Amy Litt. If blooming shifts, there is the potential for a mismatch between when the flowers are open and when pollinators are active.

“There could be fewer pollinators available for plants, a shortage of nectar for bees to eat, and seeds might not get dispersed,” Litt said. “There are many potential downstream implications of a change in flowering times.”

Though the new portal was designed with climate change questions in mind, the data will also allow scientists to answer many other questions about the state’s native plants.

Along with images of all the specimens, each record will contain information such as who collected the specimen, when they collected it, what plants were growing near it, and whether it had fruit, flowers, seeds or new growth.

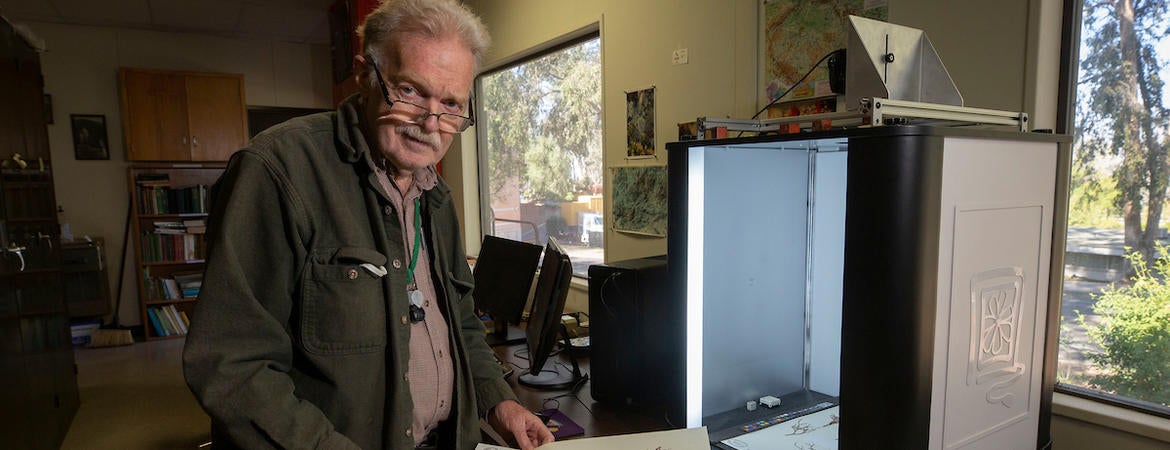

In addition, the herbarium staff is working on figuring out precise coordinates of where the plants were collected. “Some of the older specimens have very general ‘five miles north of this spot’ kind of data,” said curator Andrew Sanders.

The type of geographic information system mapping the staff is doing with the aid of herbarium volunteer Mike Cohen, is “like old fashioned mapping on steroids, and will allow for phenomenal sorts of analyses,” Litt said. “This map data can be correlated with plant distributions to understand what factors determine where a particular species is found.”

Sanders, a biologist specializing in botany, was hired 40 years ago as the herbarium’s curator. He said a portal like the one he’s now helping build would have been invaluable for his own research.

“If I wanted to know, for example, which plants in Riverside County flower in October, I had no practical way to determine that. With the new database, we can answer that question,” Sanders said. “Now people from anywhere in the world can easily look up all the records on the plants we have here.”

UCR received $75,000 of the total grant to contribute data and images for 100,000 specimens to the portal. The staff is already more than halfway done with the work — a remarkable achievement given the circumstances this year.

“Our small staff worked intensely and with phenomenal commitment to keep us on target, despite a three-month complete shut down,” Litt said.

UCR’s herbarium is the one of the largest in the state. Roughly 60% of its 280,000 specimens are from California, and Sanders would eventually like to add the entire native collection to the database.

“The first 100,000 is hopefully just the beginning,” Sanders said.