Physicists at UC Riverside have deployed and tested a novel detector prototype at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York. The six-month-long experiment, conducted during the 2024 RHIC run, marked a milestone in the development of detectors that will be used in the future Electron-Ion Collider (EIC).

EIC is a planned major new nuclear physics research facility at Brookhaven National Laboratory that will explore mysteries of the “strong force” that binds the atomic nucleus together. Electrons and ions, sped up to almost the speed of light, will collide with one another in the EIC.

The UCR group tested a prototype detector using SiPM-on-tile technology, a method that couples silicon photomultipliers (SiPM) directly to scintillator tiles. While this emerging technology has been developed by teams worldwide for various future experiments, this was the first time it was tested in a particle collider, such as RHIC.

Miguel Arratia, the team’s advisor and an assistant professor of physics and astronomy, emphasized the broader significance of the work.

“This technology will be used in key detectors at the EIC, including those that measure the highest energies and cover near-zero angles with respect to the particle beams,” he said. “They will be essential for a wide range of physics studies. These detectors must handle the most intense radiation, so we need to design them carefully.”

Weibin Zhang, a UCR postdoctoral researcher based at Brookhaven National Laboratory, explained that the team’s work at RHIC represents a key proof-of-concept for the EIC’s detector systems, ensuring they can handle the high radiation environments expected at the new facility. The prototype operated successfully throughout the RHIC 2024 run, he said, which included proton-proton collisions at 200 GeV energy.

“Being able to run a test like this at a collider is extremely rare,” added Zhang, the lead author of the research paper submitted to arXiv.

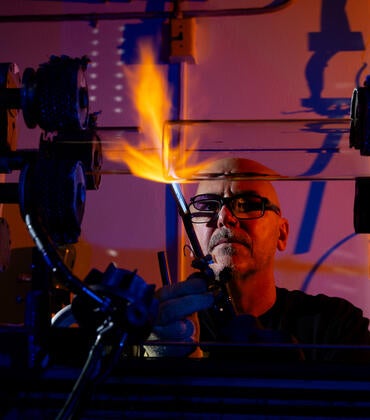

Sean Preins, a senior graduate student in Arratia’s group, said the detector is made up of layers, each containing tiles that convert energy from high-energy particles into light. This light is captured by SiPMs, allowing for detailed readings of particle showers. The detector was built and tested at UCR by a team of undergraduates, he said. The process included machining tiles, soldering components, and testing with cosmic rays.

“This experience has given our group a great deal of insight into the best way to design and assemble a SiPM-on-tile calorimeter, and we are currently applying that knowledge as we construct the next generation of our prototype,” Preins said. “We plan to double the number of channels for our next prototype, and we will be testing it at Jefferson Lab and Brookhaven Lab. As we continue scaling up our prototypes, we are getting closer and closer to the final designs of these detectors, which will be installed at the future EIC.”

The team is now preparing for the next stage of testing during the 2025 RHIC run. This phase will introduce more challenging conditions, such as gold-gold collisions, which are expected to produce higher energy density.

Arratia, Zhang, and Preins were joined in the research by undergraduate students Peter Carney, Ryan Tsiao, Yousef Abdelkadous, and Miguel Rodriguez; graduate students Jiajun Huang and Ryan Milton; and postdoctoral fellow Sebouh Paul. Carney is now a graduate student at Caltech.